- Home

- Elaine Feeney

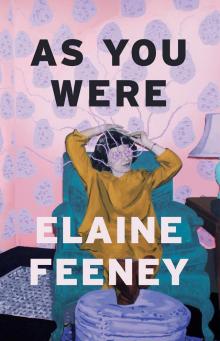

As You Were

As You Were Read online

As You Were

Elaine Feeney

BIBLIOASIS

Windsor, Ontario

Also by Elaine Feeney

Poetry

Where’s Katie?

The Radio Was Gospel

Rise

For Jack and Finn

We do not know our own souls, let alone the souls of others. Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. There is a virgin forest in each; a snowfield where even the print of birds’ feet is unknown. Here we go alone, and like it better so. Always to have sympathy, always to be accompanied, always to be understood would be intolerable.

Virginia Woolf – On Being Ill

I want to take my mind off my mind.

Mike McCormack – Notes From a Coma

Pisreógs

I didn’t tell a soul I was sick.

OK, I told a fat magpie.

She was the first beating heart I met after the oncology unit and she sat shiny and serious on the bonnet of the Volvo.

One for sorrow.

And I saluted her with that greeting you give when you find yourself alone and awkward with one magpie and she flew away, piercing her black arc through the sky blue.

An arrow points to You Are Here. This is OK.

Breathe.

You are just a dot. Swirly Space.

Breathe.

No one will ever find you.

Good. This is a good thing.

Thump.

onetwothreefourfivesixseveneightnineten

Thump.

After saluting Magpie, I sped at one hundred and thirty-nine kilometres per hour out along the M6; stone walls hurled past and end days of August conspired with night, letting a cold dusk down. Thirty-nine. Fitting. On the car’s windscreen, a fog was creeping around my eldest son’s initials, traced inside a fat heart.

But I was Fine.

Father always told me I was Fine. So as the years went by I grew increasingly mistrustful of bad-news bearers. Miss Sinéad Hynes was fine. Father said so. I was Fine. I am Fine.

I will be Fine.

By Jesus when I get my hands on her, I’ll fucking kill her; I’ll throttle her, that little cunt. She’s fine, and she pretending to be sick. Truth is, there is absolutely nothing wrong with her a’tall, but I’ll tell you what, there’s a lot wrong with the old ewe twisted on her back all night, and she didn’t even bother to check her, just even once, throw a quick eye on her. She wouldn’t mind a china cup, that one. Where is she? Under here? Here? In the cupboard? Hot-press? Come out! Come out! Wherever you are! Feefifofum. I smell blood. Where in the name of good God is she? Leaving an old ewe all the night through on her back. Reading books somewhere, and she isn’t sick, she’s fine. There’s not a thing wrong with her. Fine. Hiding is all she’s at. Afraid of work, that bitch, well, she can tell that to the dead animal, so she can, reading books. I’ll give her books when I get my hands on her.

My mother told me to have a hot bath or put on a nice hat if I was having a bad day. When I’d leave home, she’d stand in the doorway and knead the hollow space between my shoulder blades with her knuckles as I slipped past. She’d dip her index finger into the little hole at the feet of Jesus and flick droplets in my wake. He hung on a loose nail by the door, pasty and lean with bright red drips on his hands and feet, loincloth and blue eyes to die for.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Amen.

Growing up on the farm I kept bad news to myself, for going public with fortune or misfortune brings drama. I’d hide out underneath my single bed tucking the eiderdown flaps tight around me. Father’d bellow for things he needed urgently, hammer, ladder, cup of tea, plasters, jump-leads, pair of hands, mother, phone, vet. The phone for the vet was dragged in a rush out from the kitchen and my mother’d place the cream receiver into his large hand, dial for him, he’d have a palm on his forehead. Panic. Always panic.

I loved being outside with the animals, especially in the moments after they birthed; foals are the most incredible – how fast they rise and run with their mother. But I loved it best when I was completely alone with no one looking for me.

As I grew older and hair stung my armpits, spread between my legs, pimples erupting on my face, body betraying my early deftness, I borrowed more books from the library. I was clumpy and awkward and left the animals to themselves. I also stole some books from my mother’s locker. Binchy or Cookson, some Wilde with witty phrases that made me laugh and had come free with Christmas cards. Books didn’t see you. Stare at you. Notice your thick thighs that rubbed together as you moved.

Father despised all learning that came from books.

Later I read forbidden things. Just Seventeen. Judy Blume. McGahern. Edna. I longed for a Mr Gentleman to drive by, but people rarely came up our road unless they were lost or looking to buy an animal. When the house was empty, I liked to draw pictures sitting at the long kitchen table. Often birds, a fat robin landing in snow. Robins were my favourite, their blood breast and the unlikelihood of them being allowed to perch inside the house for the misfortune they’d bring on our family, all the pisreógs we hid from – putting new shoes on the table, walking under a ladder, cracking a mirror.

This power made them mysterious, cheeky outsiders. Like loner magpies.

Freeze.

My mother would cry out often about traumatic events or the threat of them. Father would say, It is no use in the wide earthly world crying alone in a darkened room for yourself.

All shock was shock, good or bad.

*

Before Magpie, I had been to Hospital a handful of times, three times to birth three boy children – the three kings. Once to have a thickened viscid appendix plucked off my bowel and once for an STD screening that turned out to be discharge from a burst ovarian cyst. Phew. You went to Hospital for a baby and it was a happy place. That’s what my mother and the neighbours said. They shared packing advice, make-up bag, fluffy bed coat, Solpadeine, Epsom salts, prune juice, new flannels, XL disposable knickers, yellow or cream clothing for baby, cream blanket with breathing holes, mittens, babygro, hat, a change of clothes and some snacks for your husband. You reacted accordingly because you knew you should be happy, it was a happy time and you’d be happy with your baby because Hospital was a gift when you went there for a baby. Any misgivings or nerves were shushed. The happenings inside maternity wards were not up for discussion.

If you were heavy all over like a small silage bale, they’d say it was a boy; if you were neat and all forward to the front, slung low like a soccer ball stuffed under your jumper, they’d say it was a girl. But all that mattered was health and happiness (and to make a bowel movement quickly and painlessly afterwards, that didn’t rupture your stitches).

Once or twice I went in secret with a drunk friend and watched as they gawked up charcoal-laced vomit out through a crow-yellow mouth, twisted ankle or a broken nose from falling over in stilettos that got trapped in Galway’s dodgy cobbles. As they spewed out sadness they grasped hard on to the steel roll of the trolley, knuckles pale and blue. I’d claw my foot along the floor and haphazardly begin apologising.

No, she’s not always like this, no, soz, I don’t know her date of birth, or soz, no, don’t know her next of kin either. Soz.

Soz.

Schuch. Schuch. Schuch.

I said over and over and overandoverandoverandtodover

wegooverandoveragain.

Schuch. Schuch. Schuch.

This was how I would herd sheep. Chanting. I use it now to control the pain.

Count it. Chant. Bellow. Watch it. Observe your pain closely.

Then, equate it into a number.

Onetwothreefourfivesixs

eveneightnineten. End. All pain

ends at ten.

I also went to Hospital to birth a daughter but we weren’t far enough along to tell whether I was low down or carrying forward or if, perhaps, I was just fat with puffy feet.

She had no heartbeat.

Schuch. Schuch. Schuch.

*

After Magpie it was impossible to focus, everything was hostile – where to fall asleep or in what position, how to avoid having sex with Alex, where to watch TV and what to watch. I flicked aimlessly through Sky Planner. I couldn’t watch the shit I had recorded on Series Link. Not now, gawping at another CSI,

or some overfed guy shoving a million meat-feast sandwiches into his mouth in a tacky Omaha deli. I couldn’t coordinate an outfit. Not one for sitting around the house. I couldn’t just listen to the radio. I was unable to do anything with sustained interest or longevity apart from cracking open boiled apple sweets between my back teeth. Though even that had its consequences as the skin on the roof of my mouth had thinned and tasted rusty from sucking the green-and-red drops.

With everything unpalatable, I froze. Ostrich. Attempted to blend in. Chameleon.

And while I understand the wacky madness of ostriches and the complex threat chameleons are under from forced domestication and threadworms, after Magpie, emulating them was the best I could muster, and yes, it was somewhat considered, and yes, many times it was neglect, and yes, I may be judged harshly for my non-disclosure of my bodily activity, and yes, at other times it was downright cruel, hiding my terminal status from Alex, but mostly it just was what it was.

Dwelling in my body had become complicated, and negotiating language for its actions and more specifically the actions of my wayward cells was far from simple, even if now I know that everything has a point of simplification.

And it was utterly bewildering.

Abjectly terrified of the complications of social relationships, it suited me to go underground after Magpie, turn in on myself. This protected me from known drama-hacks, addicts, fuck-wits, mentalists, religious, super non-religious, egoists and lack-of-ego-sap-the-ego-outta-ya-ists that cling on around the sick.

Christmas came and went. Seasons here are reliable, the way they move along, constantly motored, and while people noticed how thin I was and commented on it, they also believed me when I said it was taking some time to shake a flu virus thing.

Spring arrived, shy and reserved, with a little frost spite. Daffodils popped, snow fell, winds came, lambs dropped, crocuses hung delicately above soil, wind howled, sun shone on cobwebs, and the few old ewes that survived the long harsh winter were applauded.

I stayed at home and worked from our bed. But really I was under my duvet, Googling, in case I suddenly dropped dead and needed a soft landing spot.

I desperately wanted to pick up a book as I ran my hand along their spines over and over. But I baulked.

Maybe you might help with the sheep herding and shir it’ll take that pasty look off your face – is that infection back again? Aren’t you a lot weaker than your mother? And all those antibiotics she’s giving you. I keep telling her you’re fine, and you have to fight it yourself. You can’t keep falling in under sickness like this. Jesus Christ above in heaven, I don’t know where we got you from. Well, you’re certainly not following after my side. Fine strong people on my side, not pale city people. Weak they are, the city people, it’s the smog, or the lack of work. Both probably. If you rubbed a bit of rouge onto your sour-dough puss, you know, I declare to Christ but you might look, indeed you definitely would look, a lot better. Men don’t like to look at a pasty pale face, and you do want one at some stage I presume, because you’d hardly brave it all alone, you wouldn’t last an hour. If the toaster broke, or you had to fix a plug, what good would that Moira Binchy be then? No fucking good a’tall. You should try to fight it, for fuck’s sake, you should fight this better, with your fists or anything at all you have, you should claw your nails at it, pity you’re still gnawing them off, the nails, but you need to fight it, you’ve no fight, with your puss all pasty, a cowardly girl. Did I really rear a coward? What age are you now? Hmmmm? Age? Twelve? Nearly twelve. You’re nearly twelve? Twelve is a woman.

Fuck.

I grew meticulous in herding, obsessive, counted animals until I became dizzy and forgot the count. Start over. And over. I determined those I cared for from those beyond my responsibility. I fenced off the strays, ushered them into small verdant fields, leaving them to their sullen business deep in flaxen-yellowed ferns and beryl moss, dappled with hillocks and jaded flat thistles. There’s bad land in the West of Ireland with its vertical drystone walls that criss-cross the fields.

I hate it. The rain-soaked greenness of the fields, glum Jenga-like walls. But I like order. I separated our neighbours’ sheep from ours, identifying them by their deep ruby-red markings. H. Dark indigo-blue oily targets on their rumps. Sheep skimble/skamble unlike cattle and at times they’d run at me, big woeful eyes as though they were running to a cliff’s edge or to the slaughterhouse.

As they cut all my clothes off in the ambulance I noted how very skinny I was. I was thrilled to see my hipbones. I wouldn’t have to Google Tips on Losing Weight for the foreseeable future. But I’d continue to chat to Google under the duvet. For solace. How to Live the Pain-Free Life. Doing the Proper On-Line Will. How to Control your Dying. Safe ways to Euthanise. Last Death Rattles. Irish Health Care Cutbacks. The Rate of Incorrect Diagnostic Tests. Outsourcing of Diagnostic Tests and Positive Percentage Error. Kefir Grains. How-the-Average-Mid-Late-Thirty-Something-

With-It-ALL-Feels. The Perfect Dinner: Cheap and Superfooded. How to Stand Comfortably in Heels All Day Long. In-Hair Styles. Layers are Out. Structure In. Nail Polish Longevity. The Best Broth Recipe to Eat Cancer Cells. Chipped Your Tooth off Your Wine Glass? How to Fix It in an INSTANT. Best Fish and Chips in Galway. Why Galway is one of the Fastest Growing Foodie Heavens next to Glasgow. Why the Irish Love the Scottish but not (really) the British. How to Pronounce Quinoa. The Irish Treaty Commemoration Planned Parties and How We Feel About All of That Now We Often Shout for England in the World Cup. Dehydrating Your Nails to Help Your Varnish Stay in Place. Dehydrating Foods. UVA vs UVB Ratings on Suncreams. How Elephant-Breath is replacing Duck-Egg-Blue as the Hottest In-Life Room Colour. How You Become Antibiotic Resistant. Property Prices in Bulgaria. How to Enjoy Sex When You’re Sick. How to Enjoy Sex after a Botched Episiotomy. Are Protein Power Balls Actually Any Good For You or Do They Contain Secret Sugar? How to Get the Thigh Gap. Why the Ugly Animals’ Preservation Society is Legendary but the President for Life Element Uncovers the Dictatorial Fringes of Environmentalists. Doing an Online Will and How to Make it Toxic-Family-Proof. Doing an Online Memory Box. How the Sociopath can Manipulate the Elderly. Do Magpies Really Predict the Future? Are Magpies Prone to Sociopathic Behaviour? Detachment Theory. Is There a Way to Control the Anxiety of Thinking You’re a Sociopath? Keeping Secrets. How the Blobfish Mates. Cremation With Tooth Implants. Anxiety Testing Online.

Taking a Social Media Break.

How to Switch the Internet Off.

*

One January when I was around nine or ten, I went plucking green rushes to make my mother a St Bridget’s cross. It’s said the cross should hang in a house to ward off disease and protect it from burning down. I liked the sound of the stream near the rushes. Spluttering. Father had been threatening to burn the house to the ground due to our ungratefulness as his children, and I wanted to do something practical, for him and for the house, but mostly to cheer up my mother because she was terrified of fire. I hacked clean the first thin wild rushes, but soon began to distinguish hardy ones from lazy ones and with a gentle pinch to the exact middle of each, I heated the sap between my damp fingers, then began bending at the centre point, finally overlapping them. Limp rushes can’t prop up a cross that’s expected to save an entire family, but I was only learning. The base has to be more solid. My first attempt was slopp

y, and fell apart a little, but it cheered up my mother and became the Hynes’ Family Cross. It hangs over the front door and upon returning home, I’m reminded of my failures.

I wouldn’t fail now. I wouldn’t tell a soul.

Palliative. Doctor. Time. Tick Tock Hynes. Tick Tock.

Chapter 1

The Ward. Six-Bedded. Much Hospital Paraphernalia.

- Corticosteroids, intravenous. Wired.

- A white plastic pen from the bank that I use for cheques, not my journaling pen. No use.

- Two books. New Selected Poems by Heaney and The Gift of Mindfulness. No use.

- Heavy Astral night cream from a blue tub that I use on bikini line (not for face). No use.

- Vaseline that I use as an eyebrow dye barrier, strictly not for face. No use.

- Roger & Gallet soap. Fleur d’Osmanthus Eau Fraiche. Flowery, floral. (Way over the top, usually kept on show in downstairs loo.) No use.

- MAC Ruby Woo lipstick. Perfect but a little drying.

- Jo Malone Rose Oud perfume. Good.

- Three competing Get Well Mum cards. Too much.

- Blobfish slippers. Aces.

- iPhone 4G. Useful but patchy.

- Baby wipes. Great.

- A picture of us all at Santa’s Grotto. Fuck.

Hospital is entirely recognisable if you are into Victorian dramas or Prison Break. In Hospital you are a) Kept In or b) Let Out. You’re checked fastidiously, usually by the dinner-bringers. You’re tagged. Your clothes are removed, cut off, packed away, lost, stolen, or, perhaps like me, you may arrive entirely naked off an ambulance with only a strapless Wonderbra in the shaking hands of your husband. You no longer have a title, or hardly a name, and all recognisable connection to the past (aka the outside) disappears and is replaced by bright lights, chicken-tikka-with-light-mayo sandwiches in plastic triangular boxes, dark-chocolate-chipped-cereal-bars-with-cranberries, life-saving-Goji-berry sprinkles on salads from the Hospital shop, visitors sipping out of coffee cups, blowing their pursed lips into the tiny hole, the liquid never seeming to cool down, lots of family fighting, lots of TV shows in the Visitors’ Room doing loud Lie Detector tests on people with bad teeth, lots of brown bags full to their necks with pyjamas and impractical fluffy slippers, some ciggie breaks with copious amounts of bitching about doctors who gave the news too harshly, the doctors who gave the news too quickly, gave the news and left for coffee, and then, then worst of all, those doctors who didn’t give news at all.

As You Were

As You Were